|

I attended the last class of the summer season 99 at the Studio at the Corning Museum of Glass to learn about Moldblown Glass and refresh my skills with glass with my first class in 7 years. For the week of Labor Day, I traveled to Corning NY, for a class in mold glassblowing with Walter Evans, who makes wooden blocks and molds for over 1000 studios. This is a report on that class with discussions of the place, the methods, and the particular class. Corning is a modest sized town (14,000) in a river valley below tall overhanging plateaus that are ideal for soaring and the shared airport with Elmira is a center for soaring and making the gliders. Corning's downtown is a very nicely preserved older buildings with a lot of restaurants, glass studios, arts and knickknack galleries, an Eckerds, and sales outlets for Corning and Revere housewares. In other words, it is tasteful touristy. The edge of town along the river is dominated by the long black glass building of the Corning headquarters and across the river at the other end of a broad walking bridge is the Corning Museum of Glass including the library and the Studio. There are also a number of buildings used for research. The arrangement at the Studio is that students are housed double rooms in a Days Inn just up the river with meal tickets issued for breakfast at two places and dinner at four or five. One of the breakfast places is a bakery with light cooked breakfasts and the other is an employee food place with rather heavier meals. The dinner places range from the Glory Hole Pub with fairly good bar food (burritos, chicken breast) to Medleys, a pure vegetarian restaurant, to a Chinese restaurant, to Rouseau's a very nice classic cooking place just around the corner from the Inn. Lunch is brought in each day, something different each day with vegetarian included each time, ranging from pizza to Medley's food to sushi/teriyaki to cold cuts with rolls and bread with salad. Days Inn is a nice ordinary motel with a pool I used almost every day. THE STUDIO

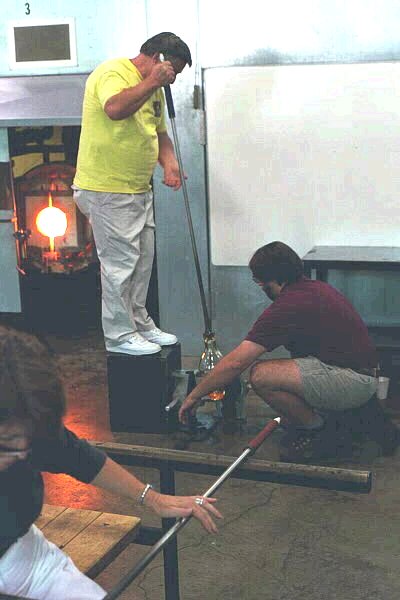

The Studio is three smaller classrooms for torch work (pic.above), kiln/paint work (pic.above) and wet mold making (not shown), a meeting/lunch/video room, cold working room, offices, and the hot glass studio (pic above & others) which occupies about half the space. The whole arrangement has windows for public observation with bleachers in the studio (PIC) and references are made in the museum to the chance to visit the Studio. (More on the Museum below - Visits.) The classes offered the week I attended were lampworked paperweights, reverse painting on glass, and moldblown furnace glass. Both students and instructors were encouraged to visit the other classes and try their hand.

For a weeklong class there are 12 three hour sessions, morning and afternoon Monday thru Saturday with practice use available from 4 to11 (and less used than I expected, I was very tired.) Representatives of the library and a curator at the museum came in at lunch. During the evening slots were provided for a tour of the museum, the Steuben blowing floor, a look at the study cases in the museum, a visit to the museum photography space, along with slide shows of instructors' work (very impressive) and student work (depressingly impressive for me.) See visit notes and classmate notes below.

Walter Evans will be celebrating his 65th birthday and his 50th year in the handblown glass industry early next year. The first 31 years involved working his way up through factory glassblowing from a bit boy to a gaffer at Pilgrim Glass. He then spent 8 years as a foreman and then switched full time to making molds, something he had started after taking a woodworking course and being asked to take over when the Pilgrim mold maker died. Walter has a lot of stories to tell about mass production of glass by hand methods and is firm in his opinion that art glass is destroying the glass factories because the factories haven't moved with the time. Until he discussed the number of people involved in making some products, I guess I did not realize how much of a factory it is. One small example: glass basket has a handle and the guy who does the handles all day has two bit gatherers working with him because it takes two people gathering to keep up with handle placer, who does nothing but that.

The class is built around the kinds of molds that Walter makes: split molds (see above) that are symmetrical around a vertical axis where the glass is placed as a hanging blob after pre-shaping and the halves are closed while the glass is rotated and inflated until it is shaped to the form of the mold. Walter's molds are turned from cherry wood which is soaked in water. Heavy use industry molds are made of iron or aluminum which is finished on the inside with a sticky goop that holds cork powder or similar material that is burned in place to provide a carbonized surface for holding the water that makes the steam surface the glass is blown against. Thus, we are not talking about two piece bottle molds with pictures of log cabins or George Washington (usually iron and hot) or three piece contact molds ("three mold blown") used to make pitchers, etc. in early 18th Century American blown glass. An important difference between the iron molds and Walter's type is that Walters much more obviously provide a starting point for working the glass. Mold blown bottles were normally taken from the mold, the neck worked briefly if at all, and the bottle annealed. Three mold blown examples include clear cases where the same mold was used to create a pitcher, a vase and a bowl, but those involve working the top of the glass and avoiding damaging the detail of the mold below. Much of what comes out of a turned mold could be done by hand on the pipe. It would take longer and not be as uniform. By using the mold, a glass worker can get to a specific starting point for further working the glass in, say, 8 minutes instead of 15 minutes, or 7 minutes instead of 20 when the piece is more complicated in shape. Some effects from a mold are simply much more difficult to keep in crisp shape by hand, like blowing the basic shape into an optic before blowing into the mold, to get the mold shape with optical ridges on it. The glass going in can be colored or have other variations. Once the piece has been molded, that may be only the beginning, with the molded part ending as only the base of a bowl, or forming the body of a vase, or making most of the shape of the piece with added lip details and wraps. Our class began with basic shaping of the glass to get the desired result. We used two basic molds: a tumbler (PIC) and a vase (PIC) Each mold was turned from a single block of cherry that was sawn down the center and hinged above a disk shaped base that formed the bottom of the piece. The problem in both molds, but particularly the straight sided tumbler mold, is that once the glass hits the wall it stops moving up or down. A thick blob of glass of too round a shape will result in the thickness hitting the wall and then the bottom moving down getting thinner and thinner because that glass at the wall is not being stretched. The ideal pattern is a necked blob that is allowed to stretch to the bottom of the mold without being inflated against the sides and then it is inflated so the center touches the bottom and the sides are blown out against the walls, actually (in a simple mold) forming the shape from the bottom up. The glass has to be kept rotating and the inflation matched to the glass forming inside the mold as revealed by the hot glass glowing through the seam and the locations of the steam coming out the vertical seams and the vent holes, gently at first, then more firmly to press into the corners. When the blower judges the glass ready, a tap of the foot signals the person holding the mold and the blowing must stop to prevent deforming the piece as the mold is opened.

A well maintained and used wooden mold can sustain 600 uses without clear damage and if a person doesn't mind the size of the mold growing, up to 2,000 impressions can be done. Obviously, mold growth is more important in trying to make matched sets of goblets (especially matching a set made a couple of years ago when one breaks). Walter says, in comparing the cost of a wood mold ($60-100) to a much more expensive metal mold ($600-800), that by the time a blower has gone through a couple of wood molds, if the design is any good, it probably has been stolen by mass production people. The hot shop at the Studio is a very nicely built fairly standard layout with the addition of extra secure areas for the public. Some people remarked on the somewhat odd arrangement where the public enters and walks in a narrow hallway behind the hot wall until reaching the outer wall of the building along which is the viewing area with bleachers, (PIC) the complaint being that if the hot wall was on the outer wall, the "wasted" space for the walkway would be part of the blowing floor. I rather liked this arrangement, because the outer wall is a window wall, giving light and with them open, ventilation and the floor was hotter than I expected. The hot wall is effectively an L shaped room with walls on both sides and ventilation on top. There is enough space to walk around the equipment and storage shelves and spaces are included, which makes the shop floor look neater. Also, with doors on the public hallway, staff can get to the space without crossing the shop floor. [Click plan for larger.]

Across a gap leading to the offices, is the start of the main wall is a vented fuming hole, followed by gloryhole, main furnace, pipe heater with color oven above, glory hole, white board, entry, pipe storage, color furnace, and glory hole. The glory holes are basically identical, one slightly bigger with two sets of overlapping doors, all with cast doors. Two roll top annealers of a discomforting design are on the fourth side of the floor. The annealers give visitors a good view of placing the glass, but the tops are very heavy and neither easy to move or to replace. Each lid actually has a rolling bridge with a cam lever that lifts the whole top up about an inch so it can pushed to one side or the other. Because of the width of the bridge (about 15") and the fact the track does not extend beyond the base, there is a space in the center that can be filled only by reaching in under the lid. Further, the lid must be exactly centered (there are lineup pins) before lowering or the safety switch that turns on and off the heating elements will stay off, chilling the annealer. The annealers are identical and made of insulating fire brick with 8 or 10 rows of elements in grooves, thus making them suitable for casting and slumping if desired. The track is not very tall and I have been told that people have knocked the bridge off the track trying to push the lid. There are three work benches on the floor for the class, each with full tools, and three marvers on wheels with good thick tops about 2x3 feet. Additional tools can be requested from the techs and we had out a table with many steel plates and kiln shelves with a rack and heavy iron tool for heating cane arrangements in the glory hole. (parsifoli? sp?) The rack for setting the plates down has a nice touch - a ball bearing swivel for swapping the plate end to end as one end tends to heat faster in the glory hole. Curiously, there are no pipe hangers and many of the punties and some of the pipes have no collar for hanging. Since most/all the names of people in the class will be unknown to readers, I will describe a few of their characteristics. The class itself had 8 people, 2 women and 6 men, plus a technical assistant who was well known to me as he comes from down the road in Austin. The distance record in our class was a guy and a gal from far southern CA (although a gal in the torchworking class was from Alaska.) Not counting my strange situation, the lowest experience guy was a year, while several people in the class had well over 10 years experience. The guy with the most public experience is probably the one who works at the Ford Museum. One gal had one of the Glass Center fellowships at Wheaton NJ. Two people came from the ends of MA, one each from NJ and PA. A part of the class was guided tours of special areas of the museum operation, including the Steuben glass factory located next to it. Bill Gudenrath led the tour of the museum itself, in the evening near closing. His historical information was especially useful. The museum, at the moment, is much reduced in size as it is being rebuilt in anticipation of its 50th birthday and the city's 150th. The historical glass shown is contained in a Best of the Corning Museum gallery, arranged as much as possible by technique, so similar work on the glass down through the centuries is gathered together in groups of six to ten pieces. Recently opened are the newest parts of the museum, including one area featuring scientific uses of glass, including the damaged blank of the first Palomar mirror disk, and another gallery of contemporary art glass. The Rakow Library is getting its own building near the Studio and space freed up is being converted to galleries.

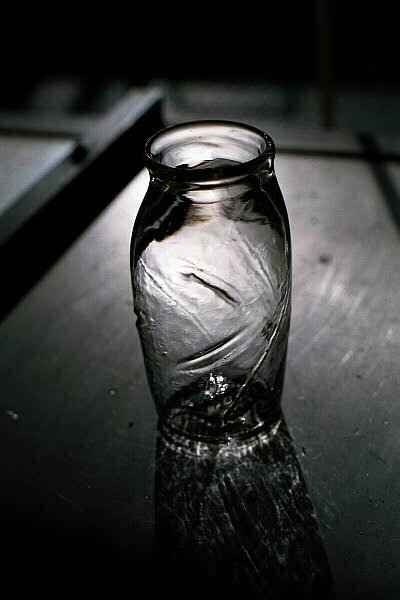

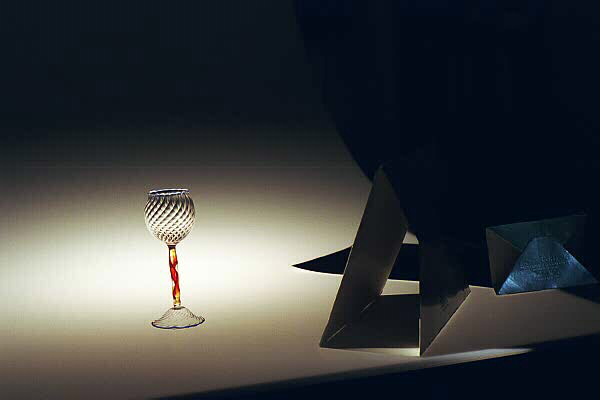

Two specialized visits were to the

photographer for the museum and the glass study rooms. The manager of the

photographic department and chief photographer, Nicholas L. Williams, showed us

his rig and set up a couple of pieces brought by students. My photos make it clear that good

lighting does great things to glass even if the camera is

handheld with fast film. He shoots slow fine grain film with long

exposures for depth of field. He uses a large sheet of white

Plexiglas sandblasted F95 on one side and lights from below as

well as all around above. He has many fairly low power lights and

snouts that fit them so he is highlighting with beams of light an

inch or less in diameter in some cases. He likes a 105mm macro

lens, but is often shooting 6x6 film format. We had a

considerable discussion of the state of electronic cameras, he

saying they are continually improving and liking one I won't name

because it might imply museum endorsement.

The glass study rooms give a suggestion as to how complete the collection in the museum really is. In a rather small space set aside from construction are a dozen or more examples per shelf, 4-5 shelves per case, 4-5 cases per row, 4-5 rows of glass. The cases are well lighted for selecting glass and specific areas (such as mold blown bottles) may include a dozen or more examples. We were able to examine several pieces closeup (without touching) and the instructors discussed features of them. For me, a highlight visit was getting out on the floor of the Steuben factory next to the museum. Not many people were working as late in the day as we visited. The steps taken to keep the glass pure and consistent are impressive: a platinum rod is moved constantly through the furnace, stopped with a foot switch for smaller gathers. Larger gathers are taken from the underneath the furnace where a stream of molten Steuben crystal runs constantly at a rate of 2 pounds per minute (the runoff into water being remelted) When a specific product/team needs a "gather" they set a switch and a worker puts a cylindrical collector in the stream for a precise time, like 2 minutes 35 seconds. The collector is spring loaded so the glass is always added to the top (not collected at the bottom then filled up the sides, possibly adding bubbles). The worker sets a switch for a light at the team and the container is raised to floor level where a worker punches a pipe into it - one "gather" for the whole piece. All the marvers and containers are highly polished and wiped before every use. Two pieces were being made during our visit, a large plate worked traditionally and a star vase that was punched in a mold and then pulled and the neck turned in a loop to the final shape. In addition, one person was making air twist stems to add to something else, pulling a cane about 15" long and getting five or six stems from the middle each cane. Our teaching assistant, Matthew Labarbara got to work some of the glass and found it so long working that it completely upset his timing. A new site for Steuben is www.steuben.com. (Cameras are not allowed on the factory floor.) By the way, the museum provides access to a close up glassblowing demo on a balcony over the factory. One of the neat points is that a series of cameras and monitors show close-ups of the work being done, including one shooting through a silica plate into the back of the glory hole. The camera views are controlled by rubber footpad switches on the floor and while the gaffer is standing on one, if the narrator steps on another, a computer selects which combination of views are to appear on the monitors, preparing for the next move of the gaffer (i.e.. show the mold while the gaffer is still at the glory hole.) HANDS ON GLASS

|

|

|

At

the end of the workshop, I went out to above the airport before my flight

and visited the great soaring hill that launches over the valley.

There is a museum and craft flying when conditions are right.

At

the end of the workshop, I went out to above the airport before my flight

and visited the great soaring hill that launches over the valley.

There is a museum and craft flying when conditions are right.